Minnesota native Tim O’Brien is a preeminent author of the Vietnam experience. His semi-autobiographical story collection, “The Things We Carried,” portrays a platoon under constant deadly threat and the emotional struggles that spring from that.

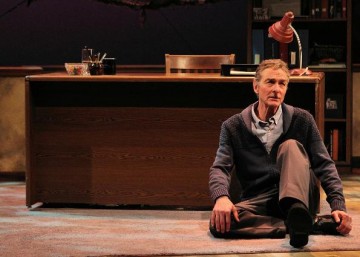

Jim Stowell has adapted the stories into a one-character play featuring Stephen D’Ambrose which opened Saturday at the History Theatre in St. Paul. It runs in repertory with “Lonely Soldiers: Women at War in Iraq” by Helen Benedict.

O’Brien’s title refers to the various items that soldiers carry while on their mission. Both necessity and superstition determine those items, ranging from canteens of water, can openers, and mosquito repellent to a rabbit’s foot, a girlfriend’s pantyhose, and the thumb of a Viet Cong teenager. It also refers to the emotional baggage of men who are viscerally aware that they may very well die.

Stowell’s somber adaptation is shaped into confessional sections that relate to O’Brien’s combat duty, his summer of discontent when he considered defecting to Canada, and wrestling with guilt over surviving while others on both sides of the conflict perished. There are luminous descriptions of nature from Vietnam to the Minnesota/Canadian border. And poetically graphic descriptions of violence — blood spread across a shirt, missing limbs, the “dainty” look of a young dead man.

D’Ambrose is superb. He probes the psyche of a man at odds with the manly duty expected of him with courageous vulnerability. The desecration of a mutilated Vietnamese corpse by his fellow soldiers repulses O’Brien and he does not take part, but he must be loyal to his comrades despite their coarse behavior.

Director Leah Cooper has ably guided the play’s various dimensions so that as melancholy as the general tone is, there is vivid contrast. In one sequence a youthful O’Brien

takes off in his car from his hometown of Worthington, Minn., toward Canada. He ends up spending time with an intuitive elderly man on the Minnesota side of the border. The man has a way of drawing out O’Brien’s darkest fears. It’s a poignant look into the anxiety of a youth torn between resisting the draft and resisting the disgrace that defection would bring.

The powerful virtue of Stowell’s adaptation is its unrelenting focus on the way war compels people to devalue the lives and the bodies of the enemy. The play’s most haunting moments reflect O’Brien’s near-obsessive torment over killing a young Vietnamese man with a grenade.

However, in a segment where he remembers the death of a soldier friend, Stowell prolongs the descriptions too much. Drama, like poetry, tends to fare better when fewer words deftly create imagery and don’t linger past their point of impact. This is also exacerbated by D’Ambrose being directed too frequently to write O’Brien’s thoughts in a notebook, breaking the fluidity of his actions and expression.

Sarah Brander’s functional scenic design contrasts an office setting with netting, suggesting a jungle camp. Wu Chen Khoo’s balmy lighting massages the painful memories evoked. Martin Gwinup’s sound design mixes familiar 1960s music with sounds of war.

John Townsend writes about theater.